E-rupee a gamechanger?

When you hold a hundred rupee note in your hand, you will see a pledge by the RBI Governor: “I promise to pay the bearer the sum of one hundred rupees” What does this pledge mean when you are actually in physical possession of the currency note?

Like most people, I too never bothered to probe this until I became governor and it became part of my job to understand the import of a promise I was making. I was told that this meant the governor is guaranteeing that the note is legal tender, and cannot be refused as a means of payment. A conscientious governor will also see this as a reminder of his duty to preserve the purchasing power of the rupee by keeping inflation low and steady.

How will the governor make this promise with the digital e-Rupee that RBI is reportedly planning to issue?

That raises a more basic question. Why are RBI and nearly a hundred other central banks around the world contemplating issuing digital versions of their national currencies – central bank digital currencies (CBDCs)?

The basic motivation seems to be fear that their money will be displaced by private cryptocurrencies that – pardon the pun -are gaining currency. In fact, central banks were quite nonchalant when bitcoin and its many clones emerged a dozen years ago. Notwithstanding their libertarian charter of freeing people from the tyranny of fiat currencies issued by central banks, this first wave of cryptocurrencies failed to replace traditional money largely because their values fluctuated widely.

Central banks see an opportunity in issuing digital currencies. The reality is that cash is on its way out because of digital payments that developed over the last two decades quite independently of cryptocurrencies. In Sweden today, it’s hardly possible to see a Kroner currency bill.

But when Facebook announced in 2017 that it was going to issue a cryptocurrency ‘Librd – since renamed Diem- central banks were jolted. Unlike the bitcoin which had no intrinsic value, the proposed Diem will be backed by a reserve asset such as the US dollar. That strength, together with a client base running into several billion, will give Facebook the clout to pull payment transactions away from domestic currencies into its own Diem, undermining the monetary sovereignty of central banks. Issuing their own digital currencies is the defensive response of central banks to this threat.

Beyond fear, central banks also see an opportunity in issuing CBDCs. The reality is that cash is on its way out because of digital payments that developed over the last two decades quite independently of cryptocurrencies. In Sweden today, it’s hardly possible to see a Kroner currency bill, while in China many people are not even aware that there are means of payment beyond WeChat and Alipay.

A similar transformation is in train here at home in India. Credit cards and debit cards have been followed by online payments, mobile apps, private wallets and now payment gateways on technology platforms such as Google Pay and Amazon Pay. What’s heartwarming is that it’s the low-income segments who are switching to the digital mode more readily and enthusiastically.

Notwithstanding their growing popularity, digital payments are costly. Our workers in the Gulf, for example, still pay hefty fees in remitting money back home to their families. Not just cross-border transactions, even domestic transactions entail large fees. We are blindsided to them because merchants distribute the fee they pay to payment platforms across their whole clientele via higher prices. By offering a universal payment platform, CBDCs will have the potential to bring prices down across the board.

If CBDCs are such a force for the good, why are central banks not moving forward more decisively? Because, apart from complex technology and design issues, CBDCs also entail downsides.

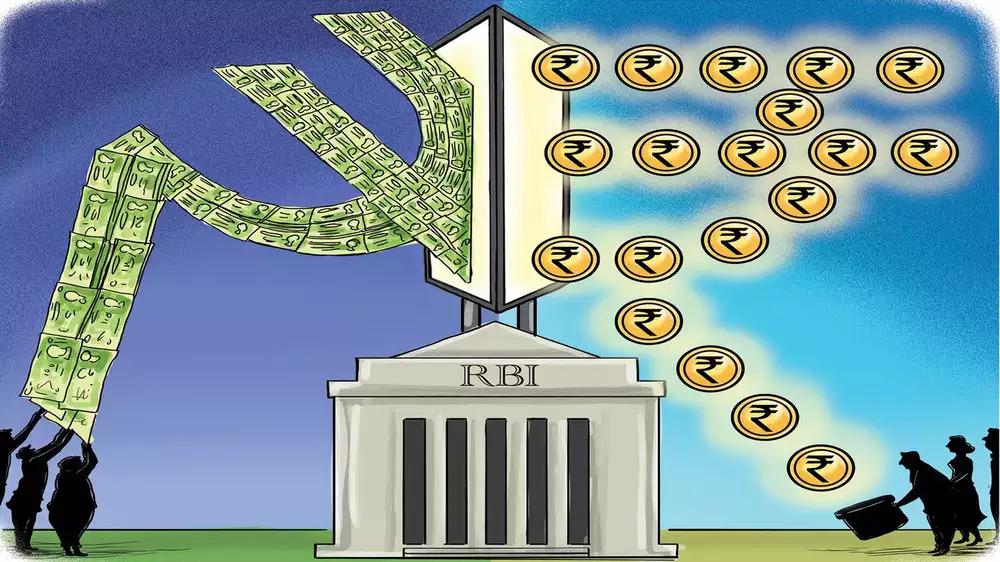

A big downside is the potential impact of CBDCs on commercial banks. Commercial banks are in the business of financial intermediation – taking money from savers and lending it to borrowers at a higher rate of interest. This process of financial intermediation has historically driven economic growth.

The fear is that with CBDCs providing accounts for everyone with the central bank – people will move their deposits from commercial banks to their accounts in the central bank. This will erode the deposit base of commercial banks, raise the cost of deposits and hence the cost of credit.

Can we afford that at a time when our growth is going to be increasingly credit-intensive? Such ‘bank disintermediation’ is not inevitable though since the central bank need not, indeed should not, offer interest on CBDC accounts.

A more realistic fear is that in times of panic, CBDCs will precipitate bank runs. We know that when a bank is seen to come under pressure, people pull their money out of that bank. Indeed, such bank runs are often set off by self-fulfilling fears. Having a CBDC account with the central bank will make it that much easier and tempting for people to move money and trigger bank runs.

Another downside of CBDCs- one that we can all relate to – is loss of privacy. A cash transaction is anonymous. When I go to a grocery store and pay the bill in cash, it leaves no trace. On other hand, a transaction in a CBDC leaves a trail. While this may prevent illegal activity such as money laundering and drug trafficking, many honest citizens might feel uncomfortable with the government being able to track their financial transactions.

One way of getting around this is to continue to issue cash even after CBDCs come into play. In fact, in a country like ours where connectivity may not be available all the time and everywhere, it’s inconceivable that cash will just disappear any time soon.

Finally, for all the potential transformative impact of CBDCs, the user experience with them will not be any different from the already existing digital payments.

And for the governor, the import of his promise will be no different either.

– Former Governor of Reserve Bank of India